Bolton Women ‘Doing Their Bit’

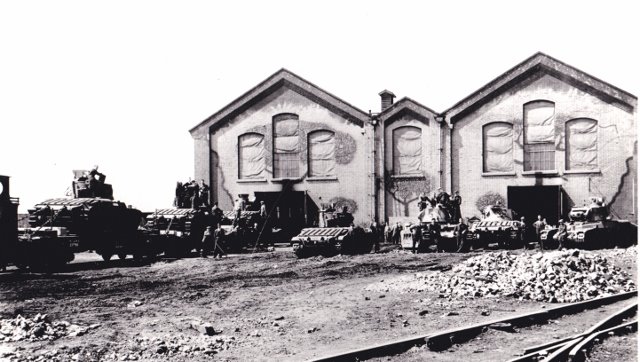

As World War One wore on, Britons responded, not just to the call to arms, but to the call ‘for’ arms. Men who, for whatever reason, could not don a uniform, instead lent their skills and strength to the manufacture of shells, grenades and guns and were joined by women. In Bolton, the local Munitions Committee declared in June 1915 that the town was ready to respond to Lloyd George’s call to set up munitions factories. A War Office official had already visited foundries and engineering shops to see how they could be adapted for war work. Lacking the hydraulic presses capable of fitting copper bands to shells, Bolton formed a link with larger neighbour Manchester to ensure the job got done.

By July, the local Bolton Journal reported that classes were being held in the engineering department of the Technical School in Bridgeman Place to train munitions workers. It was declared that in eight to ten lessons a man could master the rudiments of engineering enough to enter a munitions shop. The classes were open to all men and women between and ages of 21 to 40 and the average age of recruits was 35. Women were instructed in the ‘lighter mechanical work’ of the manufacturing process.

By 1916, Bolton was producing 5,000 hand grenades a day and 30,000 shells a week. Women assisted in production and packed grenades into boxes. A local newspaper reporter visiting one of the many local factories which had been turned over to munitions manufacture, described the grime and noise, particularly the ear-splitting shriek as steel met lathe and the skill and dedication of the operatives whose lives were ‘bed and work’. Said one, “We must face our share, for after all, we are better off than yon lads in France or in t’Dardanelles.”

It wasn’t only in munitions that women assisted the war effort, as able-bodied men left Britain for the trenches; women were ready and willing to take over the jobs they had left. However, in Bolton during June 1915 the Labour Exchange reported that there was no local demand for women workers. It was even suggested in some quarters that “the moral standard of English girls – of educated English girls too – is so low that it would be unsafe to employ them in public places side by side with educated English men clerks”!

By December though, the Bolton Council Tramways Committee was considering employing women as tram guards and a special sub-committee visited neighbouring towns where women ‘clippies’ were already working to see the style of uniform and met with a deputation from the Amalgamated Association of Tramway and Vehicle Workers to discuss working conditions for women. January 1916 saw the Tramways Committee approving the employment of female tram guards and by the end of the month twenty young women had been taken on.

Boarding their trams were other young working women whose distinctive armbands and large bags identified them as postwomen, entitled to a free ride to the start of their round or ‘walk’. In winter they carried a lamp too. These girls worked two shifts, 6am to 9am and 3pm to 6pm, for which they were paid the same wage as their male counterpart.

No-one could say the women of Bolton weren’t ‘doing their bit’.